|

Richard E. Cole, Colonel

Co-Pilot Crew 1

Cole was the co-pilot of Doolittle’s plane and the first off of the Hornet’sdeck, around 0800 (8:00 am ship time) April 18, 1942. Close to 1330 (1:30 pm ship time), they dropped their first bombs on Tokyo. They continued on toward China. At 2120 (9:20 pm ship time) after 13 hours in the air and having covered nearly 2,250 miles, Cole and the rest of his crew bailed out over China.

Cole enlisted November 22, 1940. He completed pilot training and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant, July, 1941. Cole remained in China-Burma-India until June, 1943 and served again in the China-Burma-India Theater from October, 1943 until June, 1944. Cole was relieved from active duty in January, 1947 but returned to active duty in August, 1947. He was Operations Advisor to Venezuelan Air Force from 1959 to 1962. His peacetime service included posts in Ohio, North Carolina and California. Cole rated as Command Pilot. His decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross with 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, Air Medal with 1 Oak Leaf Cluster, the Bronze Star Medal, Air Force Commendation Medal and the Chinese Army, Navy and Air Corps Medal, Class A, 1st Grade. |

| |

|

|

Robert L. Hite, Colonel

Co-Pilot Crew 16

Hite’s plane, Bat out of Hell, slid on the Hornet’s deck in the rough seas before take-off and in the process a sailor lost an arm in the propeller’s blades. After bombing Nagoya they made for the Chinese coast. After he and the crew bailed out south of Hanchung, they were captured by the puppet government forces, although Hite was the last to be caught. The Japanese executed fellow crew members Lt. William Farrow and Corporal Harold Spatz. Hite and the rest of his crew spent the next 40 months in POW camps.

Hite enlisted September 9, 1940. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant and rated as pilot on May 29, 1941. Hite was captured after Tokyo Raid and imprisoned by the Japanese for 40 months. He was liberated by American troops on August 20, 1945 and he remained on active duty until September 30, 1947. Hite returned to active duty during Korean War on March 9, 1951 and served overseas before relief from active duty again in November, 1955. Decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart with 1 Oak Leaf Cluster and Chinese Breast Order of Pao Ting. |

| |

|

|

Edward Joseph Saylor, Major

Engineer Crew 15

Saylor’s plane was nicknamed TNT and bombed an aircraft factory and dock yards of Kobe. He and all his crew escaped injury when they ditched near an island west of Sangchow, China. Lt. T.R. White, M.D., who flew with Saylor, would amputate the leg of the Ruptured Duck’s Lt. Lawson in China.

Saylor enlisted December 7, 1939 and served throughout World War II in enlisted status both stateside and overseas until March, 1945. Saylor accepted a commission in October, 1947 and served as Aircraft Maintenance Officer at bases in Iowa, Washington, Labrador and England. His decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Force Commendation Medal and the Chinese Army, Navy and Air Corps Medal, Class A, 1st Grade. |

| |

|

|

Thomas Carson Griffin, Major

Navigator Crew 9

Griffin was navigator on the Whirling Dervish. After a smooth take off and bomb run over the Kawasji truck and tank factory in Tokyo the crew headed for China. They bailed out about 100 miles south of Poyang Lake.

Griffin entered service on July 5, 1939 as Second Lieutenant, Coast Artillery, but requested relief from active duty in 1940 to enlist as a Flying Cadet. He was rated as a navigator and re-commissioned on July 1, 1940. After the Tokyo Raid, Griffin served as a navigator in North Africa until he was shot down and captured by the Germans on July 3, 1943. Griffin remained a POW until release in April, 1945. His decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters and the Chinese Army, Navy and Air Corps Medal, Class A, 1st Grade. |

| |

|

|

David J. Thatcher, Staff Sergeant

Engineer-Gunner Crew 7

Thatcher flew on Lt. Lawson’s Ruptured Duck. On take-off, the plane’s flaps were not extended and the plane seemed as if it would fall into the water. They recovered and went on to bomb an industrial section of Tokyo. He was the only member of his crew not seriously injured when his plane crashed in the water short of the beach on which they were trying to land. Thatcher’s exploits can be read in detail in Lawson’sThirty Seconds Over Tokyo.

Thatcher enlisted December 3, 1940. After the Tokyo Raid, he served in England and Africa until January, 1944. Thatcher was discharged from active duty in July, 1945. His decorations include the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with 4 Oak Leaf Clusters and the Chinese Army, Navy and Air Corps Medal, Class A, 1st Grade. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The time itself is closing the door on your opportunity to own an authentic piece of Doolittle Raid history. The story of the Doolittle Raiders’ Goblets drives that point home.

There are 80 silver goblets, one each for the 80 men who flew on the Doolittle Raid against Japan. After this year’s 69th reunion, only the five belonging to the surviving Raiders will remain upright in their cabinet, while seventy-five will be turned upside down, each representing one of the Doolittle airmen that has passed away. Over the years, these goblets have taken a highly symbolic place in the history of military aviation.

When the five remaining aviators gather in Omaha in a few short weeks, they will conduct their somber "Goblet Ceremony." Each Raider that has passed since their last reunion will be formally toasted and his goblet will be turned upside down. This year, Col. William Bower, Col Frank A. Kappeler, Captain Charles John Ozuk will be remembered. Each goblet has the Raider's name engraved twice—so that it can be read if the goblet is right side up or upside down.

A bottle of Hennessy Very Special Cognac from the year of Doolittle’s birth, vintage 1896, is reserved for when only two Raiders remain. When that time comes, those two men will drink the final toast to their departed comrades from that bottle.

The National Museum of the United States Air Force is the current home of the 80 silver goblets. The goblets were a gift to the Raiders from the city of Tucson, Arizona, presented to Doolittle during a Raiders' reunion in that city in 1959. Later that year Doolittle turned them over to the United States Air Force Academy during halftime of the Air Force-Colorado University football game.

The Goblets travel to each Raider reunion, guarded by a pair Cadets from the Air Force Academy. The portable display case used to transport them to the reunions was built in 1973 by Richard E. "Dick" Cole, Doolittle’s copilot during the raid.

|

|

|

|

|

|

As soon as Watson's plane blasted off the deck, I lined up and took off about five minutes later. I had been slightly delayed due to the continued misfiring of the right engine which finally smoothed out. The take-off was easy although I sweated out that right engine during those critical moments of the roll down the deck.

I circled the carrier once and flew parallel to it's course and set my gyro compass and compared it with the magnetic compass. We picked up a true course of 270 degrees about 500 feet off the water. About an hour and a half out Sergeant Horton, on watch in the upper turret, shouted over the interphone.

"Gunner to pilot. Twin engine plane, twelve o'clock!"

Directly ahead and above us was a Japanese patrol plane and it must have seen us at the same time because it immediately dove out of the clouds directly at us. I increased the power on both engines and swept underneath it. We quickly outdistanced it and didn't attempt to fire on it because it never really got within range. After that incident, I decided to fly the rest of the distance at altitudes ranging from 1,000 to 4,000 feet in order to avoid detection. We hit Inubo Saki right on the nose, thanks to our navigator, "Sally" Crouch. I turned south for about ten miles and then turned west across the neck of land to Tokyo Bay, then northwest as 3,500 feet in and out of scattered clouds. When I sighted my target, I dove out of the clouds, and lined up with the target at 2,400 feet and 210 mph speed. I opened the bomb bay doors and just as I did, an aircraft carrier steaming toward the Yokosuka Naval Base opened up on us with their ack-ack of presumably small caliber. Fortunately, their fire was ineffective and inaccurate. However, since we were toward the last of the bomber string, they were waiting for us and I knew it would be no picnic the rest of the way in.

We lined up on our primary target, the Japan Special Steel Company and dropped two 500-lb demos and got direct hits. One bomb hit directly in the middle of a big building and the other landed between two buildings, destroying the end sections of both. The third demo and the incendiary cluster were dropped in the heavy industrial section in the Shiba Ward.

The ack-ack fire became intense and since I had taken a long straight run on the target, by the time the bombs were out we found ourselves bracketed with the black puffs of smoke and shrapnel coming very close, generally behind but catching up fast.

Just as the last bomb went out, a formation of nine Zeros came in above us and a little to our right. I jammed the throttles forward and and went into a steep diving turn to the left to escape both the ack-ack fire and the fighters. The fighters had definitely seen us and peeled off at us but I dove under them and eluded them for the moment. We were doing 330 mph which was right on the red line. I leveled out right on the ground and hedge-hopped all the way back out to the bay. Three Nakajima 97's came out of nowhere ahead and to our left. They tried to catch us but couldn't keep up. The Zeros, however, had not been shaken. They had an altitude advantage but didn't seen too eager to come in close. I could hear Horton firing at them from the turret from time to time to discourage them. We finally shook them as I turned west across the mountains. Shortly after, a single fighter appeared alongside and above us, just as I turned south again. We fired at him with both nose and turret guns and we think we hit him but none of us was sure we knocked him down. At any rate, he got extremely discouraged which was OK with us.

Just as we thought we had made it and I had begun to throttle back when three more enemy fighters bored in toward us. I pushed the throttles forward and climbed up into the clouds to elude them. I decided to turn out to sea for about thirty miles since it looked like they were really after us. Fortunately, that was the last enemy plane we ever saw.

When we passed through the Oshima Strait and headed west, I took inventory of our damage. We had sustained one anti-aircraft hit in the rear fuselage just ahead of the horizontal stabilizer. The hole was about 7 inches in diameter; luckily no vital structural part was hit and about all it did was create quite a draft. We were also hit on the left wingtip by machine gun bullets but, again, the damage was slight. A few feet closer to the fuselage, however, and we would probably have lost gas to say the least.

As soon as we estimated we were nearing the China coast, the weather became foggy and rainy. I was forced to go on instruments about 100 miles out and stayed on them until we all bailed out. Our automatic pilot was inoperative so I had to "hand-fly" it all the way. Stork, of course, relieved me and shared the flying chore.

About the time Crouch estimated we should begin to climb to avoid the mountains along the coast we spotted an island and got a few glimpses of land as we came in over the coast. Those few glimpses gave us assurance that at least we were over land. It was now getting dark, still foggy and rainy and getting worse.

There was an overcast above us so I climbed up into it and continued on course. As we neared our ETA at Chuchow (China) I realized positively that we could never expect to make a landing in that weather so I told the crew to get ready to bail out. I climbed to 9,000 feet with about 15 minutes of gas left. I had flown deliberately past Chuchow to be sure that we would come down in Chinese territory.

I had been talking back and fourth to my crew from time to time and when I figured we had only about ten minutes of gas left, I asked Crouch to show us on the map where we were. I then gave them their instructions.

"Horton, you go first out the rear hatch," I said. "Then Larkin, then "Sally" and Stork out the front. Larkin, you wait until Horton is gone before you release the forward escape door - you might hit him. OK, fellas, that's it. I'll see you in Chuchow. Let me know when your ready back there, Ed, and good luck to you."

"OK Lieutenant," Horton answered over the interphone.

"Here I go and thanks for a swell ride."

I couldn't help but laugh at that and it made me feel good. Here we had been flying for about 14 hours, had been in combat and hit, and now had to bail out and he thanked me for the ride! Horton's spirit of discipline was typical of my whole crew and I was thankful.

I was busy keeping the plane's speed at 120 mph on instruments and felt them go one by one. They were fine men. Not one was afraid but bitterly disappointed that we had to abandon our plane. It takes men like them to win a war and that's what we were trying to do.

When the last man was gone, I rolled the stabilizer back to keep the plane from gaining too much speed and then worked myself around to get out of the cockpit. I had some trouble squeezing in between the armor plate on the backs of the two seats and had to keep pushing the wheel forward to keep the plane from stalling. I had little time to do anything once I got to the escape hatch but I did manage to grab some food and equipment before I jumped.

I dropped clear of the ship and pulled the rip cord. The chute opened nicely but just as it did the metal on one of the leg straps broke and almost dropped me out of the chute harness. I slid down and the chest buckle socked me in the chin so hard I was stunned. At the same time my pistol was jerked out of its holster and flew into space. I swung wildly for about a minute and then straightened out. Just as I did, I heard the plane hit below me and explode. A few seconds later, I hit the ground which was quite a surprise. Luckily, I was uninjured even though I had landed on the side of a steep slope.

It was raining and foggy and I couldn't see a thing. I felt I had no choice but to wrap myself up in my parachute and try to stay dry and get some sleep.

The next morning it was still foggy but the rain had stopped. When it was clear enough for me to see, I started to look for our plane. When I saw how steep the hill was that I had landed on and saw how sharp the boulders were, I don't see how I missed getting badly hurt - or worse.

The plane turned out to be only a mile away but it took me four hours to get there over the rocks and cliffs. When I got to the site of the crash there were a number of Chinese there picking in the charred wreckage. I hailed them and made them understand that I was a friend.

There wasn't a single thing I could salvage out of the wreck; it was a total loss. There was nothing to do but start walking. The Chinese farmers took me to a town where I stayed that night. The next day I met some Chinese soldiers who escorted me to Tunki, Anhwei and, a week later, Chuhsien. My crew was safe and had no serious injuries. We had a lot to be thankful for. |

Toward the Setting Sun Toward the Setting Sun

by William S. PhillipsFine Art Print I Could Never Be I Could Never Be

So Lucky Again

by William S. Phillips

The Giant Begins to Stir The Giant Begins to Stir

by William S. PhillipsFine Art Print Evasive Action Evasive Action

Over Sagami Bay

by William S. PhillipsFine Art Print

Fine Art Canvas

in-stock at Ashley's

Engaging the Enemy

by William S. Phillips

Fine Art Print

Fine Art Canvas

in stock at Ashley's

Westbound:

A Date with the General

by William S. Phillips

Fine Art Print

Fine Art Canvas

arriving soon.

Fuel State Critical -

Outcome in Doubt

by William S. Phillips

Fine Art Canvas

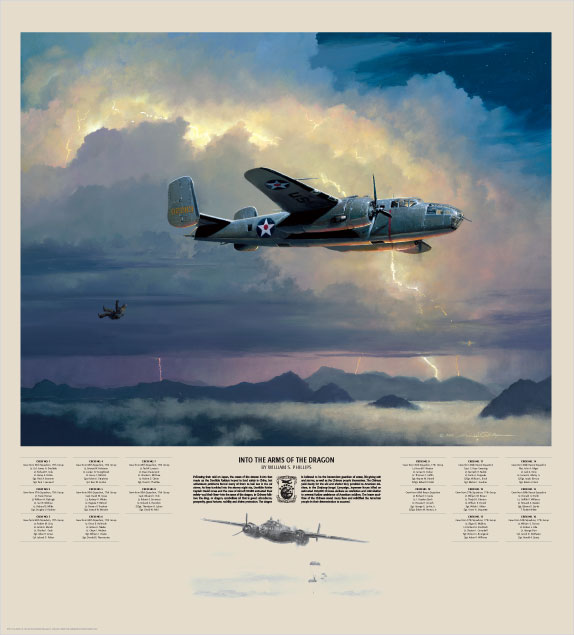

Into the Arms of the Dragon

by William S. Phillips

Fine Art Print

Fine Art Canvas

in stock at Ashley's |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In stock, framed and ready to hang in your home.

In stock, framed and ready to hang in your home.